UPDATE: Feb 21, 2022: The original blog post didn't mention the caching of custom headers. So warm cache hits would lose Cache-Control from the cold cache misses. Code updated below.

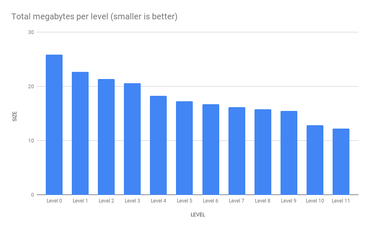

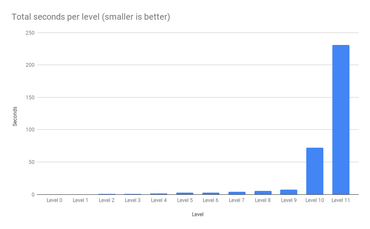

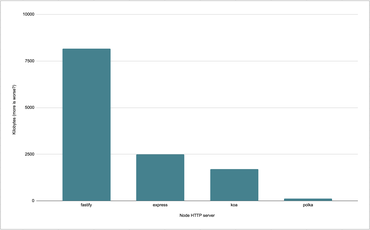

I know I know. The title sounds ridiculous. But it's not untrue. I managed to make my NextJS 20x faster by allowing the Express server, which handles NextJS, to cache the output in memory. And cache invalidation is not a problem.

Layers

My personal blog is a stack of layers:

KeyCDN --> Nginx (on my server) -> Express (same server) -> NextJS (inside Express)

And inside the NextJS code, to get the actual data, it uses HTTP to talk to a local Django server to get JSON based on data stored in a PostgreSQL database.

The problems I have are as follows:

- The CDN sometimes asks for the same URL more than once when in theory you'd think it should be cached by them for a week. And if the traffic is high, my backend might get a stamping herd of requests until the CDN has warmed up.

- It's technically possible to bypass the CDN by going straight to the origin server.

- NextJS is "slow" and the culprit is actually

critterswhich computes the critical CSS inline and lazy-loads the rest. - Using Nginx to do in-memory caching (which is powerfully fast by the way) does not allow cache purging at all (unless you buy Nginx Plus)

I really like NextJS and it's a great developer experience. There are definitely many things I don't like about it, but that's more because my site isn't SPA'y enough to benefit from much of what NextJS has to offer. By the way, I blogged about rewriting my site in NextJS last year.

Quick detour about critters

If you're reading my blog right now in a desktop browser, right-click and view source and you'll find this:

<head>

<style>

*,:after,:before{box-sizing:inherit}html{box-sizing:border-box}inpu...

... about 19k of inline CSS...

</style>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/_next/static/css/fdcd47c7ff7e10df.css" data-n-g="" media="print" onload="this.media='all'">

<noscript><link rel="stylesheet" href="/_next/static/css/fdcd47c7ff7e10df.css"></noscript>

...

</head>

It's great for web performance because a <link rel="stylesheet" href="css.css"> is a render-blocking thing and it makes the site feel slow on first load. I wish I didn't need this, but it comes from my lack of CSS styling skills to custom hand-code every bit of CSS and instead, I rely on a bloated CSS framework which comes as a massive kitchen sink.

To add critical CSS optimization in NextJS, you add:

experimental: { optimizeCss: true },

inside your next.config.js. Easy enough, but it slows down my site by a factor of ~80ms to ~230ms on my Intel Macbook per page rendered.

So see, if it wasn't for this need of critical CSS inlining, NextJS would be about ~80ms per page and that includes getting all the data via HTTP JSON for each page too.

Express caching middleware

My server.mjs looks like this (simplified):

import next from "next";

import renderCaching from "./middleware/render-caching.mjs";

const app = next({ dev });

const handle = app.getRequestHandler();

app

.prepare()

.then(() => {

const server = express();

// For Gzip and Brotli compression

server.use(shrinkRay());

server.use(renderCaching);

server.use(handle);

// Use the rollbar error handler to send exceptions to your rollbar account

if (rollbar) server.use(rollbar.errorHandler());

server.listen(port, (err) => {

if (err) throw err;

console.log(`> Ready on http://localhost:${port}`);

});

})

And the middleware/render-caching.mjs looks like this:

import express from "express";

import QuickLRU from "quick-lru";

const router = express.Router();

const cache = new QuickLRU({ maxSize: 1000 });

router.get("/*", async function renderCaching(req, res, next) {

if (

req.path.startsWith("/_next/image") ||

req.path.startsWith("/_next/static") ||

req.path.startsWith("/search")

) {

return next();

}

const key = req.url;

if (cache.has(key)) {

res.setHeader("x-middleware-cache", "hit");

const [body, headers] = cache.get(key);

Object.entries(headers).forEach(([key, value]) => {

if (key !== "x-middleware-cache") res.setHeader(key, value);

});

return res.status(200).send(body);

} else {

res.setHeader("x-middleware-cache", "miss");

}

const originalEndFunc = res.end.bind(res);

res.end = function (body) {

if (body && res.statusCode === 200) {

cache.set(key, [body, res.getHeaders()]);

// console.log(

// `HEAP AFTER CACHING ${(

// process.memoryUsage().heapUsed /

// 1024 /

// 1024

// ).toFixed(1)}MB`

// );

}

return originalEndFunc(body);

};

next();

});

export default router;

It's far from perfect and I only just coded this yesterday afternoon. My server runs a single Node process so the max heap memory would theoretically be 1,000 x the average size of those response bodies. If you're worried about bloating your memory, just adjust the QuickLRU to something smaller.

Let's talk about your keys

In my basic version, I chose this cache key:

const key = req.url;

but that means that http://localhost:3000/foo?a=1 is different from http://localhost:3000/foo?b=2 which might be a mistake if you're certain that no rendering ever depends on a query string.

But this is totally up to you! For example, suppose that you know your site depends on the darkmode cookie, you can do something like this:

const key = `${req.path} ${req.cookies['darkmode']==='dark'} ${rec.headers['accept-language']}`

Or,

const key = req.path.startsWith('/search') ? req.url : req.path

Purging

As soon as I launched this code, I watched the log files, and voila!:

::ffff:127.0.0.1 [18/Feb/2022:12:59:36 +0000] GET /about HTTP/1.1 200 - - 422.356 ms ::ffff:127.0.0.1 [18/Feb/2022:12:59:43 +0000] GET /about HTTP/1.1 200 - - 1.133 ms

Cool. It works. But the problem with a simple LRU cache is that it's sticky. And it's stored inside a running process's memory. How is the Express server middleware supposed to know that the content has changed and needs a cache purge? It doesn't. It can't know. The only one that knows is my Django server which accepts the various write operations that I know are reasons to purge the cache. For example, if I approve a blog post comment or an edit to the page, it triggers the following (simplified) Python code:

import requests

def cache_purge(url):

if settings.PURGE_URL:

print(requests.get(settings.PURGE_URL, json={

pathnames: [url]

}, headers={

"Authorization": f"Bearer {settings.PURGE_SECRET}"

})

if settings.KEYCDN_API_KEY:

api = keycdn.Api(settings.KEYCDN_API_KEY)

print(api.delete(

f"zones/purgeurl/{settings.KEYCDN_ZONE_ID}.json",

{"urls": [url]}

))

Now, let's go back to the simplified middleware/render-caching.mjs and look at how we can purge from the LRU over HTTP POST:

const cache = new QuickLRU({ maxSize: 1000 })

router.get("/*", async function renderCaching(req, res, next) {

// ... Same as above

});

router.post("/__purge__", async function purgeCache(req, res, next) {

const { body } = req;

const { pathnames } = body;

try {

validatePathnames(pathnames)

} catch (err) {

return res.status(400).send(err.toString());

}

const bearer = req.headers.authorization;

const token = bearer.replace("Bearer", "").trim();

if (token !== PURGE_SECRET) {

return res.status(403).send("Forbidden");

}

const purged = [];

for (const pathname of pathnames) {

for (const key of cache.keys()) {

if (

key === pathname ||

(key.startsWith("/_next/data/") && key.includes(`${pathname}.json`))

) {

cache.delete(key);

purged.push(key);

}

}

}

res.json({ purged });

});

What's cool about that is that it can purge both the regular HTML URL and it can also purge those _next/data/ URLs. Because when NextJS can hijack the <a> click, it can just request the data in JSON form and use existing React components to re-render the page with the different data. So, in a sense, GET /_next/data/RzG7kh1I6ZEmOAPWpdA7g/en/plog/nextjs-faster-with-express-caching.json?oid=nextjs-faster-with-express-caching is the same as GET /plog/nextjs-faster-with-express-caching because of how NextJS works. But in terms of content, they're the same. But worth pointing out that the same piece of content can be represented in different URLs.

Another thing to point out is that this caching is specifically about individual pages. In my blog, for example, the homepage is a mix of the 10 latest entries. But I know this within my Django server so when a particular blog post has been updated, for some reason, I actually send out a bunch of different URLs to the purge where I know its content will be included. It's not perfect but it works pretty well.

Conclusion

The hardest part about caching is cache invalidation. It's usually the inner core of a crux. Sometimes, you're so desperate to survive a stampeding herd problem that you don't care about cache invalidation but as a compromise, you just set the caching time-to-live short.

But I think the most important tenant of good caching is: have full control over it. I.e. don't take it lightly. Build something where you can fully understand and change how it works exactly to your specific business needs.

This idea of letting Express cache responses in memory isn't new but I didn't find any decent third-party solution on NPMJS that I liked or felt fully comfortable with. And I needed to tailor exactly to my specific setup.

Go forth and try it out on your own site! Not all sites or apps need this at all, but if you do, I hope I have inspired a foundation of a solution.