Table of contents

Use actions/github-script when bash is too clunky

bash is impressively simple but sometimes you want a bit more scripting. Use actions/github-script to be able to express yourself with JavaScript and get a bunch of goodies built-in.

- name: Print something

uses: actions/github-script@v5.1.0

with:

script: |

const { owner, repo } = context.repo

console.log(`The owner of ${repo} is ${owner}`)

Example code

This example obviously doesn't demonstrate the benefit because it's only 2 lines of actual business logic. But if you find yourself typing more and more complex bash that you, reaching for actions/github-script is a nifty alternative.

See the documentation on actions/github-script.

Use Action scripts instead of bash

In the above example on actions/github-script we saw a simple way to use JavaScript instead of bash and how it has access to useful stuff in the context. An immediate disadvantage, as you might have noticed, is that that JavaScript in the Yaml file isn't syntax highlighted in any way because it's treated as a blob string of code.

If your business logic needs to evolve to something more sophisticated, you can just create a regular Node script anywhere in your repo and do:

run: ./scripts/my-script.js

Thing is, it doesn't really matter what you call the script or where you put it. But my recommendation is, put your scripts in a directory called .github/actions-scripts/ because it reminds you that this script is all about complementing your GitHub Actions. If you put it in scripts/ or bin/ in the root of your project, it's not clear that those scripts are related to running Actions.

Note that if you do this, you'll need to make sure you use actions/checkout and actions/setup-node too if you haven't done so already. Example:

name: Using Action script

on:

pull_request:

permissions:

contents: read

jobs:

action-scripts:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- uses: actions/setup-node@v2

- name: Install Node dependencies

run: npm install --no-save @actions/core @actions/github

- name: Gets labels of this PR

id: label-getter

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

run: .github/actions-scripts/get-labels.mjs

- name: Debug what the step above did

run: echo "${{ steps.label-getter.outputs.currentLabels }}"

And .github/actions-scripts/get-labels.mjs:

#!/usr/bin/env node

import { context, getOctokit } from "@actions/github";

import { setOutput } from "@actions/core";

console.assert(process.env.GITHUB_TOKEN, "GITHUB_TOKEN not present");

const octokit = getOctokit(process.env.GITHUB_TOKEN);

main();

async function getCurrentPRLabels() {

const {

repo: { owner, repo },

payload: { number },

} = context;

console.assert(number, "number not present");

const { data: currentLabels } = await octokit.rest.issues.listLabelsOnIssue({

owner,

repo,

issue_number: number,

});

console.log({ currentLabels });

return currentLabels.map((label) => label.name).join(", ");

}

async function main() {

const labels = await getCurrentPRLabels();

setOutput("currentLabels", labels);

}

Don't forget to chmox +x .github/actions-scripts/get-labels.mjs

You don't need to go into your repo's "Secrets" tab to make ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }} available.

But imagine you want to hack on this script locally, you just need to create a personal access token, and type, in your terminal:

GITHUB_TOKEN=arealonefromyourdevelopersettings node .github/actions-scripts/get-labels.mjs

And working that way is more convenient than having to constantly edit the .github/workflows/*.yml file to see if the changes worked.

Example code

Use workflow_dispatch instead of running on pushes

The most common Actions are run on pull requests or on pushes. For actions that test stuff, it's not uncommon to see at the top of the .yml file, something like this:

name: Testing that the pull request is good

on:

pull_request:

...

And perhaps you have something operational that runs when the pull requests have been merged:

name: Celebrate that the pull request landed

on:

push:

...

That's nice but what if you're debugging something in that workflow and you don't want to trigger it by making a commit into main. What you can do is add this:

name: Celebrate that the pull request landed

on:

push:

+ workflow_dispatch:

...

In fact, you don't have to use it with on.push: you can use it with on.schedule:.cron: too. Or even, on its on. At work, we have a workflow that is just:

name: Manually purge CDN

on:

workflow_dispatch:

jobs:

purge:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

...

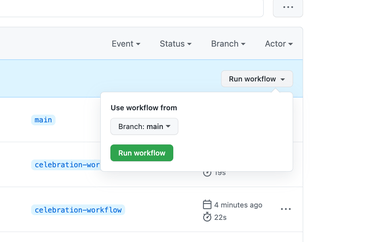

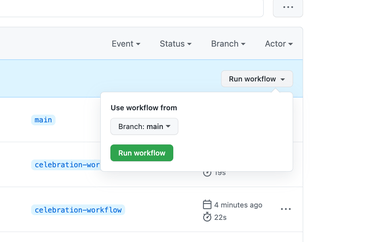

Now, to run it, you just need to find the workflow in your repository's "Actions" tab and press the "Run workflow" button.

Example code.

Use pull_request_target with the code from a pull request

You might have heard of pull_request_target as an option so that you can do privileged things in the workflow that you would otherwise not allow in untrusted pull requests. In particular, you might need to use secrets when analyzing a new pull request. But you can't use secrets on a regular on.pull_request workflow. So you use on.pull_request_target. But now, how do you get the code that was being changed in the PR? Since pull_request_target runs on HEAD (the latest commit in the main (or master) branch).

To run a pull_request_target workflow, based on the code in a PR, use:

name: Analyze and report on PR code

on:

pull_request_target:

permissions:

contents: read

jobs:

action-scripts:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Check out PR code

uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

ref: ${{ github.event.pull_request.head.sha }}

Word of warning, that will mix the pull requests code with your fully-loaded pull_request_target workflow. Even if that pull request comes with its own attempt to override your pull_request_target Actions workflow, it won't be run here. But, if your workflow depends on external scripts (e.g. run: node .github/actions-scripts/something.mjs) then that would be run from the pull request, with secrets potentially enabled and available.

Another option is to do two checkouts. One of your HEAD code and one of the pull request, but carefully mix the two. Example:

name: Analyze and report on PR code

on:

pull_request_target:

permissions:

contents: read

jobs:

action-scripts:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Check out HEAD code

uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Check out *their* code

uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

path: ./pr-code

ref: ${{ github.event.pull_request.head.sha }}

- name: Analyze their code

env:

SECRET_TOKEN_NEEDED: ${{ secrets.SPECIAL_SECRET }}

run: ./scripts/analyze.py --repo-root=./pr-code

Now, you can be certain that it's only code in the main branch HEAD that executes things but it safely has access to the pull requests suggested code.

Cache your NextJS cache

No denying, NextJS is massively popular and a lot of web apps depend on it and their Actions will test things like npm run build working.

The problem with NextJS, for any non-trivial app, is that it's slow. Even with its fancy SWC compiler simply because you probably have a lot of files. The fastest transpiler is one that doesn't need to do anything and that's where .next/cache comes in. To use it in your CI add this:

- name: Setup node

uses: actions/setup-node@v2

with:

cache: npm

- name: Install dependencies

run: npm ci

+ - name: Cache nextjs build

+ uses: actions/cache@v2

+ with:

+ path: .next/cache

+ key: ${{ runner.os }}-nextjs-${{ hashFiles('package*.json') }}

- name: Run build script

run: npm run build

If you use yarn add ${{ hashFiles('yarn.lock') }} there on the key line.

But here's the rub. If you run this workflow only on on.pull_request any caching made will only be reusable by other runs on the same pull request. I.e. if you commit some, make a pull request, commit some more and run the workflow again.

To make that cached asset become available to other pull requests, you need to do one of two things: Also run this on on.push or have a dedicated workflow that runs on on.push whose only job is to execute these lines that warm up the cache.

Matrices is not just for multiple versions

You might have experienced an Action that uses a matrix strategy to test once per version of Node, Python, or whatever. For example:

jobs:

test:

name: Node ${{ matrix.node }}

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

fail-fast: false

matrix:

node:

- 12

- 14

- 16

- 17

But, it doesn't have to be for just different versions of a language like that. It can be any array of strings. For example, if you have a slow set of tests you can break it up by your own things:

jobs:

test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

fail-fast: false

matrix:

test-group:

[

content,

graphql,

meta,

rendering,

routing,

unit,

linting,

translations,

]

steps:

- name: Check out repo

uses: actions/checkout@v2.4.0

- name: Setup node

uses: actions/setup-node

- name: Install dependencies

run: npm ci

- name: Run tests

run: npm test -- tests/${{ matrix.test-group }}/

The name of the branch being tested (for PR or push)

You might have something like this at the top of your workflow:

on:

push:

branches:

- main

workflow_dispatch:

pull_request:

So your workflow might be doing some special scripts or something that depends on the branch name. I.e. if it's a PR that's running the workflow you (e.g. a PR to merge someone-fork:my-cool-branch to origin:main), you want the name my-cool-branch. But if it's run again after it's been merged into main, you want the name main.

When it's a pull request (or pull_request_target) you want to read ${{ github.head_ref }} and when it's a push you want to read ${{ github.ref_name }}. So, in a simple way, to get either my-cool-branch or main use:

- name: Name of the branch

run: echo "${{ github.head_ref || github.ref_name }}"

Let Dependabot upgrade your third-party actions

For better reproducibility, it's good to use exact versions of third-party actions. That way it's less likely take you to surprise you when new versions come out and suddenly fail things.

But once you use more specific versions (or perhaps the exact SHA like uses: actions/checkout@ec3a7ce113134d7a93b817d10a8272cb61118579) then you'll want upgrades of these to be automated.

Create a file called .github/dependabot.yml and put this in it:

version: 2

updates:

- package-ecosystem: 'github-actions'

directory: '/'

schedule:

interval: monthly