If you're reading this, you might have thought one of two thoughts about this blog post title (or both); "Cool buzzwords!" or "Yuck! So much hyped buzzwords!"

Either way, React v16.6 came out a couple of days ago and it brings with it React.lazy: Code-Splitting with Suspense.

React.lazy is React's built-in way of lazy loading components. With Suspense you can make that lazy loading be smart and know to render a fallback component (or JSX element) whilst waiting for that slowly loading chunk for the lazy component.

The sample code in the announcement was deliciously simple but I was curious; how does that work with react-router-dom??

Without furher ado, here's a complete demo/example. The gist is an app that has two sub-components loaded with react-router-dom:

<Router>

<div className="App">

<Switch>

<Route path="/" exact component={Home} />

<Route path="/:id" component={Post} />

</Switch>

</div>

</Router>

The idea is that the Home component will list all the blog posts and the Post component will display the full details of that blog post. In my demo, the Post component never bothers to actually do the fetching of the full details to display. It just displays the passed in ID from the react-router-dom match prop. You get the idea.

That's standard React with react-router-dom stuff. Next up, lazy loading. Basically, instead of importing the Post component, you make it lazy:

-import Post from "./post";

+const Post = React.lazy(() => import("./post"));

And here comes the magic sauce. Instead of referencing component={Post} in the <Route/> you use this badboy:

function WaitingComponent(Component) {

return props => (

<Suspense fallback={<div>Loading...</div>}>

<Component {...props} />

</Suspense>

);

}

Complete prototype

The final thing looks like this:

import React, { lazy, Suspense } from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

import { MemoryRouter as Router, Route, Switch } from "react-router-dom";

import Home from "./home";

const Post = lazy(() => import("./post"));

function App() {

return (

<Router>

<div className="App">

<Switch>

<Route path="/" exact component={Home} />

<Route path="/:id" component={WaitingComponent(Post)} />

</Switch>

</div>

</Router>

);

}

function WaitingComponent(Component) {

return props => (

<Suspense fallback={<div>Loading...</div>}>

<Component {...props} />

</Suspense>

);

}

const rootElement = document.getElementById("root");

ReactDOM.render(<App />, rootElement);

(sorry about the weird syntax highlighting with the red boxes.)

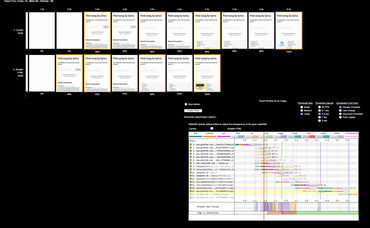

And it totally works! It's hard to show this with the demo but if you don't believe me, you can download the whole codesandbox as a .zip, run yarn && yarn run build && serve -s build and then you can see it doing its magic as if this was the complete foundation of a fully working client-side app.

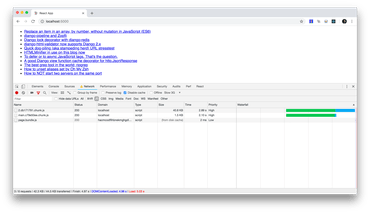

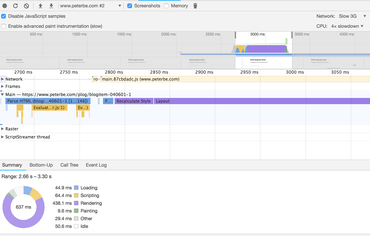

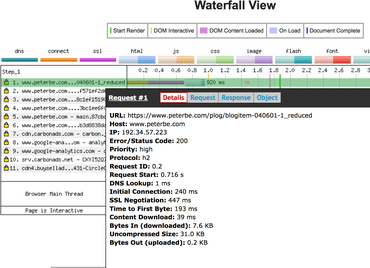

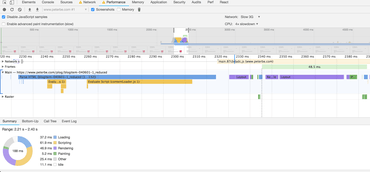

1. Loading the "Home" page, then click one of the links

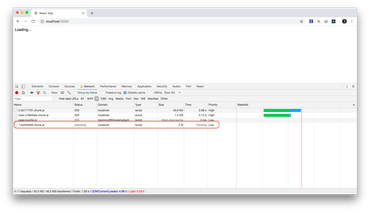

2. Lazy loading the Post component

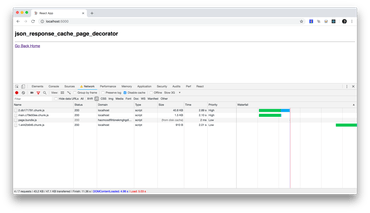

3. Post component lazily loaded once and for all

Bonus

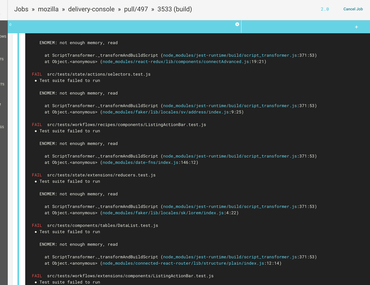

One thing that can happen is that you might load the app when the Wifi is honky dory but when you eventually make a click that causes a lazy loading to actually need to go out on the Internet and download that .js file it might fail. For example, because the file has been removed from the server or your network just fails for some reason. To deal with that, simply wrap the whole <Suspense> component in an error boundary component.

See this demo which is a fork of the main demo but with error boundaries added.

In conclusion

No surprise that it works. React is pretty awesome. I just wasn't sure how it would look like with react-router-dom.

A word of warning, from the v16.6 announcement: "This feature is not yet available for server-side rendering. Suspense support will be added in a later release."

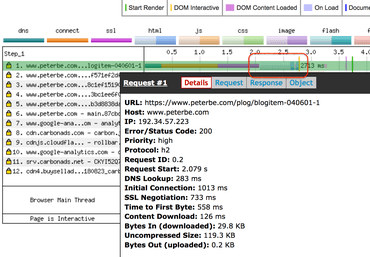

I think lazy loading isn't actually that big of a deal. It's nice that it works but how likely is it really that you have a sub-tree of components that is so big and slow that you can't just pay for it up front as part of one big fat build. If you really care about a really great web performance for those people who reach your app rarely and sporadically, the true ticket to success is server-side rendering and shipping a gzipped HTML document with all the React client-side code non-blocking rendering so that the user can download the HTML, start reading/consuming it immediately and then whilst the user is doing that you download the rest of the .js that is going to be needed once the user clicks around. Start there.